Students and Peer Learning

On this page we share helpful and inspirational work by students.

Assignment: Write a pedagogical story

In Waldorf Education, the loving care applied by teachers to their observation and safeguarding of each child’s wellbeing bears very practical fruit. One of these is the creation of original stories told to the class as a whole but inwardly aimed at one particular pupil or situation, which requires a non – confrontational intervention. This tool is particularly suitable for addressing young pupils who will respond to imagery much more directly than they would to ideas and concepts about conduct or behaviour. Here is a particularly successful example from a current student in February 2024.

Pedagogical Story

January 2024 Assignment

David Allies-Curtis

This story is intended to meet any child that is feeling on the outside of a group and that is finding it hard to join in. It also speaks to a low self confidence and a feeling of uncertainty when wanting to do something but not knowing how to. The story has elements that pertain particularly towards melancholic and phlegmatic temperaments. It was written with Class One children ( age 6/7) in mind.

Have you ever felt like you just don’t know how to do something? This is the story of Winnie, a young starling chick who, ever since the day she hatched had been aware of the big wide family that she had been born into. For even in those early days, she could hear the calls of the starlings in other nearby nests. For starlings are often very loud. So loud in fact that she could at times hear several starling families talking at once and it was hard to understand what was being said! And when that was mixed in with the sounds of her five other chick siblings in her own nest the sound was tremendous. When it came to feeding time, Winnie would chirp as loudly as she could, along with her brothers and sisters, and surely enough she would get her part of the meal, but sometimes it truly was confusing for young Winnie when everyone was talking at once. She might sit there not knowing what to say, trying her best to understand what the others were doing.

When Winnie felt like this she would often take comfort in her favourite cosy corner of the family nest. It was all she had known since hatching, and she loved it dearly. Their nest was located in the hollow of a large beech tree where, sometime in the distant past a large branch had snapped away in a storm and left a scar in the side of the tree. Many generations of starlings had made use of this site for nesting and Winnie’s father had taken great care when lining the base with many layers of soft straw. It was not a beautiful or tidy nest, but it was so warm and snuggly and Winnie new every inch of it, every strand of straw and especially right where her favourite spot was to be cosy. She would take great comfort in sitting there, especially when she was feeling worried, and Winnie did have a big worry.

Every day, Winnie’s mother and father would tell Winnie and her brothers and sisters the story of the great starling dance in the sky that they would do. It happened in different places at special times of the year and involved enormous groups of starlings all flying together in perfect harmony with each other, like one great twisting whirling cloud of birds. Winnie could feel that her mother and father dearly loved the dance more than anything and longed for the time when they could join it again. Winnie’s brothers and sisters all seemed so excited by the stories, and all wanted to join in too, but Winnie was not so sure. She liked the idea of the dance, yes to be sure, she liked the image she had in her mind of how it might look in the sky, but she always imagined herself seeing it from the ground and not as being a part of it. This was because she felt worried that she would not know how to do the dance. She had never danced! She had not even flown yet! How could she be expected to join in with the perfect harmony of thousands of experienced starlings and dance along with them?

Well, one day, after Winnie’s father was finished telling his story of a dance he had been apart of, Winnie decided to ask the question “Father, how will we know how to do the dance?”. Her father looked at Winnie and cocked his head to one side and considered this question a moment. Then his eyes smiled and he said in his strong voice “Winnie, when the time comes, you will know.” And that was all he said on the matter. Well, Winnie did not feel satisfied at all with the answer, and she continued to be worried that she would not know how to take part in the dance.

And so, time went on and the chicks grew and grew. Winnie knew that the time was getting nearer and nearer and that she and her brothers and sisters would soon need to learn to fly and join the sky dance. The wind was turning cold outside the nest hole and that meant that winter was coming. It was one of the special times of year that she had learned about when the starlings would make the great dance together each evening.

And then the day arrived. Winnie’s parents announced to the chicks that just before evening time would be the first dance of the season. Winnie’s brothers and sisters started an especially loud and excited chatter, but Winnie, feeling concerned, shuffled over to her favourite cosy corner of the nest to settle down and find some comfort. She was worried that she might be left behind if she did not join the dance, but she still did not know what to do. And so just before the evening came, father starling spoke to the chicks. “Any of you are welcome to join us in the dance this evening, but do not feel that you have to. There will be plenty of dances in the season and you will be just fine here in the nest until we return if you choose to stay”. Mother starling looked at Winnie and smiled with her eyes and then she and father starling jumped up to the edge of the nest and then flew off to join the dance. And one by one, each of Winnie’s brothers and sisters boldly jumped up on to the edge of the nest and then off they flew. Winnie waited a good long while in her cosy corner, and then finally decided to get up and have a peak over the edge of the nest. She hopped across to the entrance hole and up onto the edge. The sight that met her eyes was astonishing! She saw hundreds of starlings dancing in the sky, moving this way and that way in a beautiful motion. They seemed to expand and contract across the sky and they all seemed to move in perfect harmony. She loved way the dance looked and was struck still for several minutes, mesmerised by the show. But then the feeling returned that she felt that she could not join in, as she did not know how to. Overcome with a sudden sadness, she hoped back down into the nest and shuffled into her cosy corner.

A short while afterwards, Winnie’s brothers, sisters, mother and father returned to the nest, full of excited chatter about the evening’s dance. Mother starling could see that Winnie was feeling left out and she went over to snuggle next to her. She gently preened some of Winnie’s back feathers and said simply “there will be many more dances over the next days, Winnie.” Winnie said nothing, but could feel the cosy protection of her mother’s warm body.

The next day, Winnie’s brothers and sisters could talk about nothing else all day but the dance that would happen that evening. And not only that, but Winnie could also hear the sound of the other birds in nearby nests also chattering loudly about the dance that was coming that evening. She stayed put in her cosy corner all day, but when evening came and the birds started to leave for the dance she couldn’t help but feel curious. From inside the nest the sound of the starlings dance sounded even louder than yesterday. Winnie hopped up onto the nest edge once more and saw many more birds this time dancing. It was a truly wonderful sight to behold but after several minutes Winnie once again started to feel sad that she could not join in. This time though, she decided to do something different. “If I can not fly in the bird dance, then I will fly the other way and see what I can find.” And so Winnie, took to the sky and began to fly in the opposite direction from the sky dance.

Before too long, Winnie saw another young bird flying and she thought to herself “there is another starling that is not going to join in the sky dance just like me. I will go and see if she wants to play with me.” But before she could get close to the bird, it changed direction suddenly and flew off back towards the flocks of dancing starlings. Winnie flew on further and spotted another bird up ahead that was also flying the same way as her. Again, she tried to catch up with the bird, but this time it suddenly changed direction and flew upwards, high into the sky. Winnie continued on her way and before long, she saw a third bird ahead that was flying the same way that she was. This time, Winnie managed to catch up and who turned out to be a young bird, just like her. Winnie introduced herself and the two birds started a game of catch, where they would each take it in turn to follow the other. Winnie found that she could fly very well, and that with the slightest adjustments of her wing feathers she could change direction very quickly and she enjoyed both leading and following in their game.

Before long, Winnie and her friend were joined by a third bird who saw them and wanted to join in their game. This young starling flew up to them and introduced himself and the three started playing chase all together. Winnie found that the game was a little harder when there were two birds chasing her, but that made it all the more fun. And then another bird flew up to join them in the game. And another. And another. Winnie now started to get a little worried that the game is getting too big and so she suddenly flew higher in the sky to move away, but of course all of the other birds followed her instantly as they felt that it was part of the game. As they were higher and could be seen more easily, another small group of starlings that were playing their own game of chase flew over and joined in with Winnie’s group. And then Winnie suddenly understood. They are not just playing a game of chase. They were all dancing together. They were doing their own sky dance. A wash of relaxation flowed over Winnie’s entire body and her eyes glinted with the happiest smile. And then at that moment, a starling further along the group made a sudden move and Winnie instinctively moved with the others to follow them. She called out as loudly as she could “weeeeee” as she remembered what her father had said – “When the time comes, you will know” – they twisted and turned and looped and took it in turns to move and lead the dance and Winnie could see that she was an important part of shaping how the dance goes.

And so Winnie’s group now flew closer to other smaller groups of starlings that joined in with them and the dance group become bigger and bigger and they moved to join the biggest group, where Winnie’s brothers and sisters and mother and father were dancing. By now this group had become many thousands of starlings and Winnie was delighted to be a part of the movements, flowing in and out, up and down and she even decided to make some sudden movements of her own, which resulted in the dance following her for a time.

That night, as the dance came to an end, Winnie turned back to home and settled back into the nest. She was the first one home and so shuffled into her snuggly corner. She decided not to say anything at first when her family came home so that she might surprise them, as she thought that they would probably think that she stayed in the nest the whole time, but when they all arrived back father starling spoke to the family. “Tonight, I have a new story to tell you all about the sky dance. This is the story of a young starling who was once very concerned about the dance, but who went on to lead her very own beautiful sky dance”.

All the family settled into their most snuggly positions and looked briefly at Winnie as the story began, and she knew that they had all seen her take part and at points, lead in the dance.

Assignment: Following the student Craft weekend, describe the role of the hands in education

The Role of Hands in the Educational Process

Deanna Newell-Gush, July 2023

(2022 student)

Introduction

Education is a complex activity that is intended to foster the intellectual, emotional, social, and physical growth of learners, all in tandem. Within this intricate education structure, the hands stand out as a highly active and influential factor that significantly contribute to the success of education (Holstermann et al., 2010). Hands allow people to interact with their surroundings, control items and freely express themselves because of their exceptional tactile and motor capabilities. Not only are the hands useful in modern education, but also in the historical context. Hands have played a crucial role in human development and invention throughout history (Holstermann et al., 2010).

The hands have always been at the center of the most revolutionary discoveries and innovations, from the artisanal achievements of ancient civilizations to the limitless technology that we are exploring today. Touch and dexterity are powerful tools that help human beings traverse their environments, learn new information, and grow as a group (Holstermann et al., 2010). The positive contributions of hands can also be seen in hands-on activities such as pottery which facilitate mental, physical, and emotional development through direct experience.

Due to the undeniable significance of the hands scholars and teachers alike have come to appreciate the value of physical activity in the classroom. Ernst Bühler’s writing “From Play to Work” is one of the valuable resources that illuminate the transforming power of play and experiential learning. Learners can tap into their natural curiosity, spark their creativity, and hone their problem-solving skills by actively handling objects and materials. In addition Bernard Graves’s talk on evolved intelligence stresses the importance of integrating sensory data and cognitive processes through experiential learning. Besides, Rudolf Steiner’s philosophical views provide even greater depth to our appreciation of the hands’ role in learning. Steiner’s First Teachers Course offers interesting insights into the hands’ function as a link between the physical world and the mind. Activities that require the use of one’s hands are excellent for fostering not only a well-rounded education but also self-control, determination, and the freedom to express oneself. In order to gain more understanding of the role of hands in education, this essay explores the role of this crucial body part from personal experience and as perceived by various scholars.

One’s Reflected Experience in Crafting Pottery

Students gain the most from a learning experience when they use their senses and hands to explore and manipulate real-world materials and things. I have first-hand experience in making pottery, and I can reflect on my experiences to shed light on how hands contributed to my learning process. I have seen first-hand the positive effects of pottery creating on a child’s mental, physical, and emotional growth. By delving deeply into the material world of pottery, we set off on a path that shapes our educational experiences by cultivating sensory awareness, spatial cognition, and fine motor abilities (Klamer, 2012).

One of the contributions of pottery to learning is it enhances attention to detail among learners. Making pottery encourages a close relationship with the materials. The more I work with the clay, the more I can feel its texture, temperature, and malleability. My sensitivity to touch has been greatly enhanced by the many hours that I’ve spent working with clay, and glazing. This heightened sensitivity has helped me notice and value subtleties in my surroundings outside the sphere of ceramics.

Understanding spatial relationships and proportions is crucial in pottery manufacturing, and requires both spatial cognition and creative problem-solving (Klamer, 2012). As I help glaze the clay, I imagine the finished product in my mind and then bring it to life. It’s like a dance of creativity as my hands, eyes, and brain work together to paint the clay with glaze and place it into the kiln with its high heat In order to create what I see and what I imagine in my mind (Hetland et al., 2015).

The technique has helped me to visualize and handle three-dimensional objects, an achievement relevant in the fields of mathematics, engineering, and architecture, among others.

Due to the difficulty of the work required, pottery is a wonderful approach to enhance your fine motor abilities. As I work with the clay, my fingers get stronger and more dexterous, allowing me to make finer and clearer adjustments. Fine motor abilities, including hand-eye coordination and manual dexterity, can be greatly improved by the practice of pottery making (Hetland et al., 2015).

Many academic activities, including writing and drawing, require one to have complete command over ones hands at all times. It is also worth noting that making pottery is more than just a technical process; it’s also a way to express one’s innermost thoughts and feelings while practicing mindfulness (Hetland et al., 2015).

I never imagined that clay is fired in a kiln with a chimney where it undergoes several physical and chemical changes as a result of the high temperature, where the process of firing transforms the malleable clay into a durable and permanent ceramic material. The firing process transforms the malleable clay to something so beautiful that it takes your breath away. The firing of the clay is where the magic happens, it goes through an intricate journey as it undergoes a fiery transformation where there are both physical and chemical changes that occur in the kiln.

So, what happens to the clay during the firing process? The process consists of water removal, chemical changes, decomposition of organic materials, sintering, vitrification and colour development. It all depends upon the firing temperature and the duration of the heat, it is dependent on the type of clay used and this will determine the outcome of the desired look and feel. I learnt that different firing techniques such as oxidation or the reduction of the atmospheres in the kiln, can be a further factor in the final appearance of the fired clay.

We built a kiln with the guidance of our teacher who explained the process of firing clay, working with our hands and through teamwork and problem solving when the chimney was not smoking enough to provide the right temperature for our clay. We remade part of the kiln again, making a bigger hole for the chimney which provided the right environment for the clay to fire. I imparted my feelings, ideas, and goals into this team building project.

Making and firing the clay is a form of therapy because of the positive effects it has on the mind, body, and spirit (Klamer, 2012). This all-encompassing method of teaching acknowledges the value of encouraging students’ emotional intelligence and giving them opportunities to express themselves creatively.

Ernst Bühler in his “From Play to Work” discusses the need to offer children to engage in activities rather than only lessons in order to memorize (Bühler, n.d). John Dewey’s comment, which emphasized the use of one’s hands in learning, is consistent with Bühler’s viewpoint. In light of Bühler’s beliefs, hands-on activities encourage both experiential learning and active participation in the classroom. Hands-on learning provides youngsters with a direct and sensory-rich experience with materials and objects (Bühler, n.d).

This kind of participation arouses their interest, inspires them to go out and learn more, and lets them piece together information from their own experiences rather than just reading about it.

Learning that is more directly applicable to real-world situations is enhanced by the active participation that comes from working with one’s hands.

Bühler posits that the gap between abstract ideas and their practical application can be closed through children’s hands-on problem-solving, creation, and other practical activities (Bühler, n.d). Teachers can help students retain information and apply it in practical settings if they provide them opportunities to engage with the material hands-on.

Bühler adds that children who use their hands in class learn more and feel more in control of their own learning. Children develop and improve abilities, including fine motor control, hand-eye coordination, and analytical reasoning through hands-on play (Bühler, n.d). Children gain self-assurance, independence, and the ability to take initiative when they are actively engaged in the learning process.

Another importance of hands in education, which Bühler appreciates, is the child’s ability to stimulate one’s imagination and sense of play. Children’s natural creativity blossoms when they are encouraged to explore, experiment, create, and express themselves via the use of their hands (Bühler, n.d). Children’s creative potential flourishes when they are given the opportunity to engage in hands-on activities that spark their curiosity about the world around them.

Bernard Graves’ presentation: Will Developed Intelligence.

In his talk on developed intelligence, Bernard Graves highlights the importance of the hands in learning by stressing the importance of integrating sensory input and cognitive processes through hands-on inquiry. One of Grave’s major arguments is about sensory integration, where he posits that students are able to combine tactile experiences with cognitive processes through the use of hands-on exercises. Students’ numerous senses are stimulated at once when they use their hands to investigate and handle materials. Learning benefits from this multimodal approach because it facilitates a deeper, more holistic comprehension of course material.

The scholars also argued for the ability to instil learning by doing as facilitated through hands-on investigation, which encourages students to actively engage with the physical world. They state that through engaging in such experiential learning, students can move from theoretical understanding to practical application. The ability to remember and absorb information is much improved when students are able to physically engage with the material being studied.

Hand-eye coordination and other fine motor abilities can be honed when students actively use their hands in the classroom, according to Graves. He stresses that hand muscles and dexterity can be improved by carefully handling items. Besides, involvement and learner empowerment are fostered through hands-on activities. Individuals become active agents in their own learning when they use their hands to explore, create, and engage. Motive and understanding are improved as a result of students’ heightened curiosity and control over their own studying.

Rudolf Steiner: First Teachers Course, Methods of Teaching

This offers valuable insights regarding the importance of using one’s hands as a teaching tool. Steiner argues that the hands act as a conduit between the learner’s external environment and his or her internal reality (Rawson, 2021). People engage with their surroundings by touching and manipulating things with their hands. Learners are able to make meaningful connections to the world around them through their participation and the experiences they get from these interactions that shape their thinking.

Practical, hands-on activities are highly valued by Steiner because of their potential to promote holistic learning experiences. According to Steiner, it is through engagement in hands-on activities that learners tandemly activate their senses, emotions, and intellect (Rawson, 2021). As such, learning is more holistic when the hands are used as tools for experiencing, producing, and expressing. On long-term individual achievements, Steiner argues that working with one’s hands for a higher purpose promotes personal growth and discipline (Rawson, 2021).

Students gain attention, patience, and determination as they work on a task with their hands. Hands-on pursuits, with their emphasis on slow, deliberate motions, are excellent for developing self-discipline and sticking with a task until completion.

Steiner recognizes the value of manual expression as a means of expressing artistic and creative impulses (Rawson, 2021). He argues that students develop their innate creative potential through participation in artistic pursuits, which provide a tangible outlet for their thoughts, feelings, and aspirations. Learners are able to do all three of these things and more by participating in artistic activities, including painting, sculpting, and crafts.

Rudolf Steiner, First Teachers Course, Anthropological Foundations

Steiner’s emphasis on the significance of hands in learning extends to his “First Teachers Course,” specifically lecture six on anthropological foundations. In his discussion of how children learn to think and reason, he delves into the hands’ intimate relationship to brain development (Steiner, 2020). He argues that via hands-on play, children develop skills in sensory exploration, spatial reasoning, and problem-solving. He adds that hands are instrumental in merging theoretical and practical considerations. True education should promote rather than discourage the separation of theoretical study and hands-on training (Steiner, 2020).

Students are better able to apply what they learn in the classroom to real-world situations when they have opportunities to put their theoretical knowledge into practice through hands-on learning activities.

Just like other scholars Steiner recognizes the value of engaging in hands-on activities for the development of fine motor skills. He says that training one’s hands helps one become more precise, coordinated, and deft with one’s hands (Steiner, 2020).

He also reiterates the importance of using one’s hands as a means of expressing one’s personality and creative potential. Students develop their aesthetic senses and channel their inner artists via hands-on art projects like drawing, painting, and making (Steiner, 2020). Steiner believes that encouraging creativity helps people develop their imaginations and strengthens their appreciation for the finer things in life.

The ethical and moral development of learners can also be aided by engaging hands during one’s educational process. Steiner argues that doing morally and ethically sound work with one’s hands helps one develop a sense of ethics (Steiner, 2020). Learners build empathy, compassion, and a feeling of social responsibility through physically engaging in acts of kindness, cooperation, and service to others as manifested by activities on their hands. Hands-on experiences can help students develop morally by giving them real-world opportunities to put their newly acquired knowledge into practice.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that the hands play a pivotal role in the instructional process. We can attest first-hand to the fact that learning to make pottery, firing greatly improves one’s sense of touch, sense of balance, and sense of spatial orientation. According to Ernst Bühler, learning is most effective when students actively participate in the process. In his talk, Bernard Graves emphasizes the importance of engaging all of one’s senses and processing information cognitively. Additionally, educationalist Rudolf Steiner’s thoughts highlight the significance of the hands in bridging the inner and outside worlds, encouraging self-discipline, and strengthening the will. Teachers may foster students’ all-around growth and comprehension by realizing and capitalizing on the power of hands-on learning.

References

Buhler, E. (n.d). The transformation of play and learning processes during early childhood into joy in work. The significance of the hands.

Hetland, L., Winner, E., Veenema, S., & Sheridan, K. M. (2015). Studio thinking 2: The real benefits of visual arts education. Teachers College Press.

Holstermann, N., Grube, D., & Bögeholz, S. (2010). Hands-on activities and their influence on students’ interest. Research in science education, 40, 743-757.

Klamer, A. (2012). Crafting Culture: The importance of craftsmanship for the world of the arts and the economy at large. Erasmus University of Rotterdam.

Rawson, M. (2021). Using artistic, phenomenological and hermeneutic reflective practices in Waldorf (Steiner) teacher education. Tsing Hua Journal of Educational Research, 37(1), 125-162.

Steiner, R. (2020). The first teachers course. Anthropological foundations. Methods of teaching. Practical discussions.

Assignment: Exploring the Waldorf Approach to Literacy (December 2022)

Alex Brew 30.12.22

Literacy

“Literacy fits like a glove on the hand of orality.”[1] The Waldorf Curriculum

As Waldorf educators, we might imagine the quote above could only belong to the educational theories of the Steiner approach to literacy. In fact, the basis of literacy teaching in mainstream education also claims to be the “cultivation of oral skills”[2] and so, according to the national curriculum for primary education in England and Wales the spoken word “underpins the development of reading and writing”[3]. Similarly, both systems cite the richness or “quality and variety of language”[4] that students come into contact with as central to the development of literacy. Both systems have also grappled with the use of phonics, spelling and whole word methods to teach literacy, with Steiner advocating a merging of the three methods so that the child moves from detail of phonics to “wholeness”[5] of the whole word approach. And while the combination of methods by using sight words combined with phonics is frowned upon in the teaching of literacy by some phonics proponents who say that a mixed approach causes “enormous confusion”[6] to many children, a mixed approach is nevertheless used in mainstream education[7]. The broad differences between Waldorf and mainstream education, which I will explore in more depth below, lie in the realm of the balance of priorities. In my view it is this balancing act of values and priorities through the daily practice and delivery of orality and literacy that creates such vastly different educational environments.

While both systems agree on orality as key to literacy, the Waldorf system reveals the centrality of the idea through its exclusion of reading and writing until Class 1 (the mainstream equivalent of Year 2). The Waldorf teacher’s role of cultivating “a strong culture of orality”[8] as the basis for literacy is arguably more obviously a central feature in the Waldorf classroom even once literacy has been formally introduced in Class 1. Entering a Class 4 classroom in my first week as a teaching assistant, I was awed to find most children able to recite and memorise huge tracts of text including complex verse and song each morning.

The foundational importance of orality is also seen with the notion that writing is a skill separate from the task of teaching and learning and so most of the curriculum can be accessed without recourse to reading, for many years. This is something I have in fact witnessed with a Class 4 child who is supported with her undiagnosed dyslexia through reading interventions but also through the use of orality in the classroom itself. The tradition of using orality as the basis of learning and the importance placed on rhythmic time, which fosters high levels of phonological awareness, is strong within the Waldorf system and continues throughout primary education.

In Waldorf education orality is seen to be key to imagination because it activates picture formation in the child. The imagination is developed through the use of fairytale, fable, myth and epic stories as core teaching materials because “[o]ral consciousness is mythic”[9]. This helps the child blend the oral, mythic, imaginative consciousness with the developing rational and analytic consciousness of literacy. Therefore, story-telling is woven into main lesson content along with, recall of legend, fairytale and fable, the recitation of verse and poetry as well as, of course, writing, reading and drawing.

The urgency with which literacy is introduced within mainstream education has traditionally been felt less in the Waldorf approach and this has allowed this centrality of orality and gentler approach to literacy. The national curriculum of England and Wales states that if in Year 1 (the equivalent of Waldorf’s last year of kindergarten) the child is unable to decode and spell, the matter needs to be addressed “urgently through a rigorous and systematic phonics programme”[10]. This directly contradicts the Waldorf approach which is more “gradual and multisensory”[11]. In Steiner schools it is usual to delay writing and decoding until Class 1 (Year 2) because Steiner believed it was important to the child’s overall development to wait until at least the changing of the teeth in the 7th year before introducing the alphabet. In more recent times though, with the introduction of WRAT[12] and other tests in many Steiner schools, this sense of urgency and its accompanying “stress, anxiety and guilt”[13] is beginning to take its hold.

In Waldorf literacy programmes, feeling and soul development are prioritised and balanced with skill development. And so, while in mainstream education the feeling life is generally treated separately from literacy through well-being and emotional intelligence exercises, in Waldorf schools it is prioritised in every part of the curriculum. The balance between feeling and soul development on the one hand and skill development in literacy on the other is central to the approach. As such, the Waldorf practitioner introduces letters through “lively characters”[14] in drawings, paintings and texts. These kindle warmth and a sense of familiarity with this otherwise abstract system we call the alphabet. The concept that a grapheme can represent many sounds may be introduced by simply stating that a letter can represent more than one sound as in the ‘Sounds Write’[15] phonics programme or this can be done with a “feeling gesture”[16] using a poem. A drawing of a fish becomes the symbol ‘f’ by way of a story about the origins of our writing system in pictograms. By introducing reading through writing and writing through form drawing, the child sees the alphabet in its “human context” with its “ artistic roots”[17] and this creates in her a love of learning that links “communication and communion”[18]. While pictures are used to aid letter recognition in mainstream education, the use of art to contextualise and smooth the path to writing and reading is left untrodden. The Waldorf method “speak[s] to the soul”[19] and develops the “spirit-soul”[20] of the pupil because the steps towards literacy follow “the evolution of human consciousness”[21] where “phonetic script developed out of picture script”[22]. The different balance of priorities again produces a different educational environment.

While the focus on teaching literacy through orality has many strengths, it may not cater to all learning styles. There may need to be scaffolding provided to those who do not learn aurally, orally or even kinaesthetically. Another criticism could be that the focus on orality and the delay in reading may create a “Matthew Effect” where children who initially struggle “avoid reading”[23] because of the difficulty involved in it and the gap widens exponentially. However, if we are able to resist the literacy panic we may notice the benefits of the centrality of orality to the teaching of literacy in terms of the child’s appreciation of language, their use of metaphor and ability to narrate complex stories using a rich and varied vocabulary. This appreciation of the whole must be conveyed to critics of the approach who see value only in the ability and speed with which a child can decode.

Another possible weakness is that Steiner’s approach to literacy is based on the Germanic transparent alphabetic code rather than the complex anglophonic system where our grapheme phoneme correspondence is more complex. Writing is an “abstraction”[24] that must be taught and, at least in anglophone countries, cannot be easily and quickly picked up through exposure alone. With the widespread introduction of systematic phonics systems this appears to be being addressed. An exciting development I have seen in my own practice working with dyslexic children is the move from the use of ‘Sounds Write’ readers to the use of Martin Hardiman’s Waldorf readers, which offer a more poetic and artistic introduction to reading. While the Sounds Write programme feels efficient and well planned out, their readers are not greatly improved from the “boring, repetitive texts”[25] popular in the 60s and 70s. When I was able to switch over to Hardiman’s Waldorf texts, the child engaged with me over the pictures and rhythmic verse, which lends itself to a freer flow. Although the text didn’t always make as much obvious sense, it was imaginative and sparked the child’s interest enough that her reading improved significantly. Unfortunately there appears to be nothing for her age group now that she has finished those texts.

And finally, the fact that literacy in Waldorf education rests so heavily on “[e]pic, myth”[26] may lead critics to view it promoting outdated, traditional or unhelpful values. For example, the image of St. Michael slaying the dragon sits uncomfortably with modern psycho-emotional theories that promote integrating rather than eliminating parts that we may see as harmful[27]. Additionally, there are issues in terms of race and immigration, class, gender and sexuality embedded in this and other myths and legends traditionally used within Waldorf settings. For example, the idea of “driving the dragon out of our land” in the play has an unpleasant tone when performed on a public green in the middle of one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the world – London[28] – with its intense history of racist and resurgence post-Brexit. In my experience, Steiner schools are updating their libraries towards inclusivity and are making some steps towards grappling with how the stories within the classroom or festival-setting are told. In particular, I have noticed that while in mainstream and Steiner schools there continues to be a heteronormative and racial bias[29] within lessons, there is a strong intention towards change and CPD[30] to support it. I believe that getting this right is especially important in Steiner schools where the teacher has such authority and long-term influence on the child’s development.

In conclusion, the approach used in Waldorf schools seems to me to be engaging, artistic and full of life and movement. Many of the so-called weaknesses only appear to be deficits due to a myopic view that insists on the urgency of reading attainment. However, there are also much needed developments in the teaching of literacy across all educational systems as we continue to encounter and counter the ways that racism, classism, sexism, heteronormativity and capitalism influence our teaching of literacy in schools.

[1] Avison, K., The Tasks and Content of the Steiner-Waldorf Curriculum p105

[2] Avison, K., The Tasks and Content of the Steiner-Waldorf Curriculum p105

[3] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425616/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.doc (section 7 – 7117)

[4] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425616/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.doc (section 7 – 7117)

[5] Avison, K., The Tasks and Content of the Steiner-Waldorf Curriculum p108

[6] McGuinness, D, A Prototype for Teaching the English Alphabet Code, Reading Reform Foundation UK. http://rrf.org.uk/pdf/nl/49.pdf [accessed 28.12.22] p18

[7] https://www.twinkl.co.uk/teaching-wiki/sight-words [accessed 30.12.22]

[8] Avison, K., The Tasks and Content of the Steiner-Waldorf Curriculum p106

[9] Avison, K., The Tasks and Content of the Steiner-Waldorf Curriculum p105

[10] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425616/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.doc (7121)

[11] Ward. W., In Zonneveld, F., The Waldorf Alphabet Book, p58 https://archive.org/details/waldorfalphabetb0000zonn/page/n57/mode/2up?view=theater [accessed 28.12.22]

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wide_Range_Achievement_Test

[13] Ward. W., In Zonneveld, F., The Waldorf Alphabet Book, p58 https://archive.org/details/waldorfalphabetb0000zonn/page/n57/mode/2up?view=theater [accessed 28.12.22]

[14] Ward. W., In Zonneveld, F., The Waldorf Alphabet Book, p56 https://archive.org/details/waldorfalphabetb0000zonn/page/n57/mode/2up?view=theater [accessed 28.12.22]

[15] https://www.sounds-write.co.uk/ [accessed 29,12,22]

[16] Ward, W., Zonneveld, F., The Waldorf Alphabet Book p60 https://archive.org/details/waldorfalphabetb0000zonn/page/n57/mode/2up?view=theater [accessed 28.12.22]

[17] Steiner, R., Methods of Teaching Lecture 1 p28

[18] Ward. W., In Zonneveld, F., The Waldorf Alphabet Book, p62 https://archive.org/details/waldorfalphabetb0000zonn/page/n57/mode/2up?view=theater [accessed 28.12.22]

[19] Steiner, R., Methods of Teaching Lecture 1 p29

[20] Steiner, R., Methods of Teaching Lecture 1 p28

[21] Wildgruber, T., Painting and Drawing in Waldorf Schools p85

[22] Wildgruber, T., Painting and Drawing in Waldorf Schools p85

[23] du Plessis, S., “Matthew Effect” in Reading: Why Children with Reading Difficulties Fall Farther and Farther Behind, https://www.edubloxtutor.com/matthew-effect-in-reading/ [accessed 28.12.22]

[24] Avison, K., The Tasks and Content of the Steiner-Waldorf Curriculum p105

[25] McGuinness, D, A Prototype for Teaching the English Alphabet Code, Reading Reform Foundation UK. http://rrf.org.uk/pdf/nl/49.pdf [accessed 28.12.22] p17

[26] Avison, K., The Tasks and Content of the Steiner-Waldorf Curriculum p106

[27] https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/making-the-whole-beautiful/202202/how-parts-work-helps-us-get-know-ourselves [accessed 30.12.22]

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnic_groups_in_London

[29] https://neu.org.uk/advice/lgbt-inclusion-members [accessed 30,12,22]

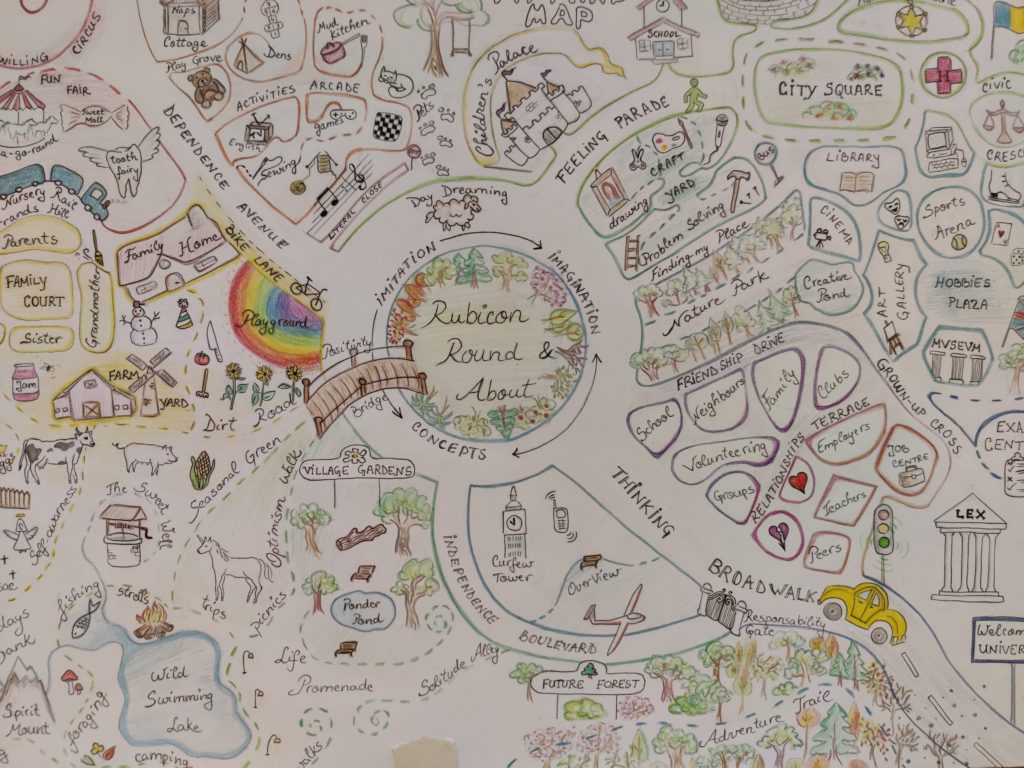

Assignment: Produce a map/diagram/chart/graphic/timeline which shows your understanding and knowledge of how child development proceeds from 0 to 21. (September 2021)

Graphic designed by Anca Paraon, 2021 student

Assignment: To what extent do I regard myself as a free being? To what extent do I experience myself as a spiritual being? How might the two be related? (January 2022)

Essay by a 2021 student:

To what extent do I regard myself as a free being?

I am going to consider how free I perceive myself to be in terms of my physical being, soul being and spiritual being. Am I free in my physical form? My physical form has many needs for example I require water, oxygen, food, sleep, to be the right temperature, and to be able to excrete waste products to survive. These are all very fundamental needs and in this basic way I do not feel free of my physical body. Arguably I do have a choice to for example completely refuse say food, water, or sleep if I decided to do so; thankfully I have never been in a situation where I felt minded to do so. That said in another way I do not endlessly eat food or drink water, so I do have control of my intake of water and food and of course I do choose to get out of bed every morning and when to go to bed at night. That said, even here there are limits to my choices for example normally I’ve got to get up for work, to look after my family and so on. Again, though it’s arguably because of the choices I’ve made in the past, for example to have a child, that I now must get up and look after him. In this way I would say I have “situated freedom”, I make choices within the parameters and framework of the life I have chosen to lead but also a life which has been influenced by the choices other people have made and also from external environmental factors. From the policies of governments to natural phenomenon like storms and to the truly microscopic level for example from the impact of viruses and bacteria.

Is my soul free? This is a very complex question and one which I suspect many philosophers have grappled with through the ages, but the question is do I regard my (soul) self as a free being? Again, my feeling is to say no, that I don’t regard my soul to be completely free. All the soul choices I make are the result of my conscience, which to a great extent was shaped by my up bringing. I was brought up in a “church” family. Not piously religious of the type my mum experienced as a child in Scotland. She went to her grandmother’s every Sunday, and the children were not allowed to run around or play or even read a book not even the bible. My childhood experience of Christianity was in contrast a very positive one. We went to church every week (without fail), to the badminton club, to the youth club, to the choir, to scripture union classes. The church was our family and our social life, but a branch of Christianity, the URC or United Reformed Church which was very ecumenical and to cut a long story short, I was brought up in an environment of safety, love and fellowship which of course impacts upon my soul. It could be argued that I had the freedom to reject these values, but I am not sure that it would be so straightforward to do that, I think they are very deeply ingrained in me (not indoctrinated, that would be a very unfair way of portraying it) but ingrained to the point where I am not even aware they are there for me to reject them. So, when I consider the soul decisions I have made in the past, I think, I did have free will, but at the same time I couldn’t have made a different choice.

I think I need to give an example to explain what I mean. About 15 years ago I was walking home from work, and I saw this youngster of about 11 years old, with a drunk lady who had collapsed and wet herself on the street quite close to my house. As I walked near a youth cycled past in the other direction and made a horrible comment to the pair. I could not have walked on by, I stopped and helped. It turned out the child was the nephew of this lady, and she was an alcoholic. Together we got her back to my house, I found a clean pair of trousers for her, and whilst she was changing, I spoke to the child to check he was ok and what the situation was. When my husband got home, he felt I was wrong to have done this, that I had put myself at risk, but to this day, I know I could not have “not helped”. That simply was not an option. So back to the question in hand “is my soul free”? No. I don’t think my soul is free. This is because I think it has been shaped by my past and by the values I was brought up in. I believe that my soul being also has “situated freedom”. It is bounded in a similar way to my physical being by my past choices and by the impacts of other people choices upon my life together with all the other situations which go to collectively make up my personal psyche.

Regarding the freedom of my spiritual being. This is the hardest question of all to answer not least because I believe Steiner himself said that to a large extent the spirit is not really knowable; if I’ve correctly understood what I’ve read so far. Of all the parts of our being this should be the freest since it is not limited by either physical or emotional need. However, I’m not sure if I am an accurate judge of whether my spirit is free as I am not sure if I have full access to it, which rather neatly brings me onto the next question.

To what extent do I experience myself as a spiritual being?

I have found this is a very complicated question to answer because I am not sure that I have enough understanding of what you mean by “spiritual being”. Here our recent tutorial was very helpful, talking with other students on the course about how they interpret this question. In our group two of the members had long associations with Steiner schools, whilst two of us are very new having only really been introduced to this since September. Reflecting on this I would say that for me, it is way too early to answer this question with any great clarity. I am still in a state of moratorium and trying to assimilate what I have learnt in the last five months. If you can imagine how somebody might feel if they woke up tomorrow and they were told that a new continent had been discovered? That is how I feel at the moment, and I think it takes time to absorb all this new information.

If, as one of our group members, who went to Steiner school, explained, spirituality is like a journey; looking back there are key points in my life that this would apply to. For example, in 2017 my husband was offered a job in Leeds. That year (2017) my son was in years 5 and 6 at school and so the move would mean a brand-new start for us all at the same time as he was due to start secondary school. We spent much of the summer holidays and autumn looking for a house and planning our life up there. It seemed like a good move as I was really worried about my son starting secondary school in Cardiff. By the first week in December 2017 everything appeared to be in place, the house, the school, the job. We were to stay in Cardiff for another six months and that week we had a meeting with my son’s new violin teacher. It was a memorable meeting, and as I left, I thought, “well if for some reason we did end up staying in Cardiff, everything would be ok”, because I could see that this new teacher would been a brilliant positive role model for my son. Within three days of that meeting and thinking that thought, everything fell through, the house, the job and the move but I knew everything was going to be ok. As it turned out I was right in more ways than I could have guessed and bizarrely I think that even things like me taking this course now actually stem from that point. So, if that is what’s meant by experiencing myself as a spiritual being, then I can see that could be the case.

On the other hand, another member of our group, who had been associated with the Steiner school for 20 years, said they felt that spirituality was more to do with having a role or a drive. If that is the case, then again, I would say a lot of the choices I have made during my life would fit in that pattern. For example, the jobs I have taken have been motivated much more by a sense of having a positive impact on people’s lives rather than to make lots of money. I am not sure if that is down to my temperament or if that is that my spirit guiding me, but as I said earlier the whole concept of the spirit is very new to me, so it is difficult for me to say.

How might the two be related? I think the two are highly related. I suspect a person who feels more physically free than I do also feels more spiritual. I do not feel free and I think this is maybe why I don’t see my own spirituality. When I was a youngster, I was addicted to TV. Growing up in the 70’s my viewing was limited to two hours of children’s TV, plus a plethora of 50’s black and white films (Flash Gordon, numerous westerns and of course Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes) and of course the Open University programs that were screened at 6am in the morning. One OU program that stuck in my mind was about physics or maths. In it, the lecturer said the following “imagine you were not a 3D being but a 2D being”. There was an accompanying graphic that showed two squares bumping into each other and generally interacting. “Now imagine that a 3D object comes and pushes you out of your dimension into a 3rd dimension. You wouldn’t know what has happened simply because everything about you means you do not have any capacities to interpret it. You cannot comprehend a third dimension because nothing about your biology would allow you to do this.” Due to this I feel I cannot discount concepts, like a spirit, just because I have not previously acknowledged them in myself, but I can see that if somebody is able to perceive their spirit then it would be, by necessity, intertwined and related to their free being.

How might this be relevant to my role as a teacher of children?

I think being more aware of myself is highly relevant to being a teacher of children, because to acknowledge this dimension in myself means I have to acknowledge this in other people, including the children I will teach. I think this is important because it changes the role of the teacher from being one of purely educating (delivering knowledge) to being one of nurturing the understanding, growth and development of the whole child. Therefore, I think it will make me a better teacher to acknowledge this even though I don’t fully comprehend this at the current time.

Assignment: Having studied Steiner's "Kingdom of Childhood", describe how a teacher’s educational actions can either enhance or compromise a child’s healthy development. (April 2022)

Presentation created by Lisa Westwood, 2021 student